Filling Up Your Inbox with Goodies—PyderPuffGirls Episode 4

In the previous posts, I covered how to set up scheduled jobs for SQL queries. How can I get a note when things go wrong? How can I send the result to myself? Email, of course! So, in this post, I will show you how to send emails with Python.

The example

I’m using Gmail as an example because it is easy to set up a throwaway account. If you can find out what the email server’s address is for the service you are using, then you should be able to replicate the steps.

Because this series is about an analyst’s workflow, if the job succeeded in the scheduling process from Episode 3, I want to send an email that has a short message with a report (.csv) as attachment.

My goal is to wrap everything into a function send_email

- that can go to multiple recipients, and

- gives me an option to attach files.

A Note on Gmail: to make this function work with Gmail without using OAuth 2.0, you need to turn “Allow less secure apps” on in Gmail settings, otherwise Google will not allow logging in. I recommend making a throwaway Google account if you decide to use Gmail to follow this post.

If you are on a private email server, however, then this is not a problem because OAuth 2.0 is a Google only security protocol.

Let’s get more notifications!

Let’s get more notifications!

Requirements

Nothing! Everything here comes with the Python (>=3.6) installation.

The code

Here’s the complete code. I’m putting the code up front so it is easier to copy-paste, but I’m going to break down in the next section.

This example uses Gmail, smtp.gmail.com with port 465, as the email server (SMTP), but you can change it to a private server and port.

import os

import smtplib

import ssl

from email.mime.text import MIMEText

from email.mime.application import MIMEApplication

from email.mime.multipart import MIMEMultipart

from pathlib import Path

def send_email(username, password, recipient, subject, body, attachment=None):

"""Send email via Gmail

:param username: Gmail username that is also used in the "From" field

e.g. pyderpuffgirls@gmail.com

:param password: Gmail password

:param recipient: a string or list of the email address of recipient(s)

:param subject: the subject of email

:param body: the body of email

:param attachment: a string or list of the path(s) of the file(s) to attach, default: None

"""

smtp_server = "smtp.gmail.com"

port = 465

ssl_context = ssl.create_default_context()

# https://stackoverflow.com/questions/8856117/how-to-send-email-to-multiple-recipients-using-python-smtplib

if isinstance(recipient, str):

recipient = [recipient]

recipients_string = ', '.join(recipient) # e.g. "person1@gmail.com, person2@gmail.com"

# create email

email = MIMEMultipart()

# Add body, then set the email metadata

if body is not None:

content = MIMEText(body)

email.attach(content)

email['Subject'] = subject

email['From'] = username

email['To'] = recipients_string

if attachment is not None:

_add_attachments(email, attachment)

with smtplib.SMTP_SSL(smtp_server, port, context=ssl_context) as conn:

conn.login(gmail_username, password)

conn.sendmail(username, recipient, email.as_string())

print(f'Sent email to {recipients_string}')

pass

def _add_attachments(mime_part: MIMEMultipart, file_paths):

"""

Add attachment to the email object from file paths

"""

if isinstance(file_paths, str):

file_paths = [file_paths]

for file_path in file_paths:

file_name = Path(file_path).name

with open(file_path, 'rb') as file:

part = MIMEApplication(file.read())

part.add_header('Content-Disposition', f'attachment; filename={file_name}')

mime_part.attach(part)

return mime_part

if __name__ == '__main__':

gmail_username = os.environ['GMAIL_USERNAME']

gmail_password = os.environ['GMAIL_PASSWORD']

send_email(

username=gmail_username,

password=gmail_password,

recipient='pyderpuffgirls@gmail.com',

subject='Some subject',

body='some message',

attachment=['test-image.png', 'send_email.py']

)

Breaking it down

I’m not going to walk through the code in order because that was not how I built it.

Instead, I will break the code down by showing you how I came up with the code and in the order that I wrote it.

There are three steps that I need to complete my code:

- connect to an email server

- send a plain text email

- attach files

1. Connecting to an email server

The first thing that I needed to figure out was how to log in to Gmail. Emails use the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), and Python comes with smtplib as part of the standard library to deal with SMTP.

I googled gmail smtp server and looked into the settings. Based on what I saw, I needed to use

smtp.gmail.comas the server address465as port

So, after storing my password in environment variables (see Episode 2), I tested the code in Jupyter notebook:

import smtplib

import ssl

username = os.environ['GMAIL_USERNAME']

password = os.environ['GMAIL_PASSWORD']

with smtplib.SMTP_SSL("smtp.gmail.com", 465, context=context) as conn:

conn.login(username, password)

print('hi')

The with block is a context manager—same as opening a file back in Episode 1. Without a context manager, I need to close the connection the function smtplib.SMTP_SSL returns. e.g. the code would look like this

conn = smtplib.SMTP_SSL("smtp.gmail.com", 465, context=context)

# ... some email code ...

conn.close()

Sometimes I forget to and the connection will leave hanging for hours. This is how you get server administrators to yell at you and block you. Using context manager means I don’t have to remember .close() my connection

Although my SMTP connection code looked fine, running it gave me an SMTPAuthenticationError.

This was confusing. So, I googled around and found that I need to turn “Allow less secure apps” off in the Gmail settings. This is a Google specific setting that does not apply to other email servers.

Now my code went through.

After logging in to Gmail, the next step was to figure out how to send a plain email.

2. Sending a plain text email

To send a plain text email, I needed 4 things:

- Name of sender

- Recipient

- Subject

- Body

Subject and body are optional, but I think it’s better to require them. The best way to put an email together in Python is using the MIME objects from the email library. In this case, to send a plain email, I can use the MIMEText object to take care of all 4 things.

from email.mime.text import MIMEText

with smtplib.SMTP_SSL("smtp.gmail.com", 465, context=context) as server:

sender = 'Mojo jojo'

recipient = 'pyderpuffgirls@gmail.com'

subject = '😠'

message = '😠😠😠!'

email = MIMEText(message)

email['Subject'] = subject

email['From'] = sender

email['To'] = recipient

server.login('pyderpuffgirls@gmail.com', password)

server.sendmail(sender, recipient, email.as_string())

Printing out the email object

print(email)

showed

Content-Type: text/plain; charset="utf-8"

MIME-Version: 1.0

Content-Transfer-Encoding: base64

Subject: =?utf-8?b?8J+YoA==?=

From: Mojo jojo

To: pyderpuffgirls@gmail.com

8J+YoPCfmKDwn5igIQ==

As I can see, MIME is a special format. To send it via SMTP, I can convert it to a Python string (the email.as_string() part)

server.sendmail(sender, recipient, email.as_string())

When I checked my sent email in gmail.com, this is what I got:

So it worked! Finally, the last thing I needed to figure out was how to attach files.

3. Attachments

Attaching a file requires more than MIMEText. It turned out I can create a MIMEMultipart object to combine the MIMEText object from 2 and an MIMEApplication object that gives me the attachments.

The steps to attach a single file are:

- opening a file in binary mode with

MIMEApplication: a binary file means it is a string that human can’t read, say a.pngimage file. -

adding the header

Content-Dispositionto myMIMEobject:Content-Dispositionis a special keyword forMIMEthat tells Python I want to attach a file either- as a file, or

- as an inline object.

In this case, I want to add my file as an attachment, so I specified

attachmentandfilename. - combining the “attachment object”

MIMEApplicationwith my mainMIMEobjectMIMEMultipart.

from email.mime.multipart import MIMEMultipart

from email.mime.application import MIMEApplication

# An empty email object

email = MIMEMultipart()

# Make an attachment object

with open(file_path, 'rb') as file:

attachment = MIMEApplication(file.read())

attachment.add_header('Content-Disposition', f'attachment; filename={file_name}')

# Add the attachment object to the empty email object

email.attach(attachment)

# Add message body, etc as in 2

content = MIMEText('😠😠😠!')

email.attach(content)

email['Subject'] = '😠'

email['From'] = 'Mojo jojo'

email['To'] = 'pyderpuffgirls@gmail.com'

with smtplib.SMTP_SSL("smtp.gmail.com", 465, context=context) as server:

server.login('pyderpuffgirls@gmail.com', password)

server.sendmail(email['From'], email['To'], email.as_string())

This is what I saw in Gmail after sending:

I can send emails now! But I want to reuse my code, so I better put them into a function.

Optional: Combining the 3 steps into a function

Now you know the steps I took to write the code. Feel free to go back and read it again:

Development workflow

I want to talk a little more about how I put the code together as it may help.

Most of the time, I test my code first in a Jupyter notebook before putting them into a function in a .py file. My thought process for the send_email function went like this

- I want to wrap my code into a function.

- Attachments are optional

- The function should be able to handle multiple recipients and attachments

Wrapping into function

When I was putting send_email together, the part about attaching files was optional, and adding 10 lines of optional code into the main function will be confusing to me in a few months. I decided to wrap it into its own function _add_attachments().

In other words, instead of writing

def send_email():

...some code...

...10 lines of code that adds attachments...

...some more code...

I decided to bundle my code as

def send_email():

...some code...

_add_attachments()

...some more code...

def _add_attachments():

...code...

What should go into a function? In my opinion, each function represents a single action or a single concept. In this case, adding attachment is an optional action, so it makes sense to make it into a function.

The lack of switch in Python

In writing _add_attachments(), first I checked if the file path is a string (a str) or a list using the Python base function isinstance(). If it is a string, then I convert it to a list. Then for each path in the list, I add the attachment to my MIME object.

def _add_attachments(mime_part: MIMEMultipart, file_paths):

"""

Add attachment to the email object from file paths

"""

if isinstance(file_paths, str):

file_paths = [file_paths]

for file_path in file_paths:

file_name = Path(file_path).name

with open(file_path, 'rb') as file:

part = MIMEApplication(file.read())

part.add_header('Content-Disposition', f'attachment; filename={file_name}')

mime_part.attach(part)

return mime_part

The if ...: statement is actually more like a case when statement in SQL. Most programming langauges have a switch-case control flow, but not Python. In Python, people use if-else to imitate the switch-case flows.

Question: what is that underscore in _add_attachments?

In Python, a single underscore prefix for a function or a variable means that the developer wants to hide it from the user. Most IDEs will autocomplete those functions in the import statements, but you can still use them.

In other words, it is a way to tag a function and tell others “this function is for internal use. If you want to use it, use at your own risk.” Here is a great post about the underscores in Python names.

Optional arguments in functions

A common way in Python to make an argument optional is to set the default to None. In this case, I wrote

def send_email(..., attachment=None):

...

if attachment is not None:

_add_attachments(...)

...

Because attachment is None by default, when I don’t put attachment=something in send_email(), Python will check my if statement and skip the _add_attachments() part.

Question: attachment is not None?

Using is not None instead of != None is also a Python convention. There is nothing wrong with using != (performance difference is negligible.) is is rarely used outside this special occasion because it checks the id instead of comparing values. Here is a link to a StackOverflow answer for the difference between is and ==.

- A rule of thumb: use

isinstead of==when it is aboutNone.

Multiple recipients and attachments

I wanted to let send_email() take both string and list as input for recipients, but email['Subject'] can only take string. What should I do?

The solution is, again, checking if recipient is a string, then do something if it is not:

if isinstance(recipient, str):

recipient = [recipient]

recipients_string = ', '.join(recipient) # e.g. "person1@gmail.com, person2@gmail.com"

Question: why not isinstance(recipient, list)?

In other words, why didn’t I write it this way?

if isinstance(recipient, list):

recipients_string = ', '.join(recipient)

else:

recipients_string = recipient

Don’t they do the same thing?

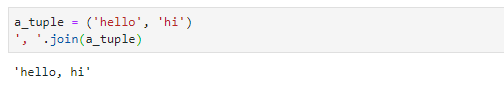

My answer is: “Yes, but…” My reason for checking str instead of checking list is that the .join() method can take sequence objects other than list. For example, I can also join a tuple.

There are other sequence objects in Python besides list and tuple, but introducing them is out of scope for this tutorial.

For me, it makes more sense to write this way. But I think it is more of a personal preference. If the code works and solves your problem, then it is good code.

What’s next?

Over the last 4 episodes, I covered 4 topics:

- How to open and write to a file

- How to submit a query to a database

- How to schedule a job

- How to send an email

Integrating those 4 into my workflow saved me lots of time—now I can run stuff at night and read my report in the morning. In my opinion, the first half of PyderPuffGirls is a win.

At this point, myself from two years ago would be pretty happy.

The second half

There are few things that comes to my mind, in no particular order:

- Making it pretty: a

.csvis nice. But my clients want their reports in Excel. How can I format my.csvinto an Excel spreadsheet? - Long queries: the queries shown here were short, but what about long and complex queries? What’s the best way to deal with them?

- How to use an IDE, say PyCharm, for efficient Python development?

Let’s see how far we can go after Christmas.

More PyderPuffGirls

Please feel free to post in the comments section or tweet at @ChangLeeTW for questions or comments.