A Python Tutorial for the Bored Me—PyderPuffGirls Episode 1

This is the Episode 1 of the PyderPuffGirls†—a tutorial on automating the boring parts of data analysis that we are going through in the next 8 weeks. I’m writing this tutorial for people that had at least one false start in learning Python, just like me two years ago.

A tutorial for people who had a false start?

Where I got the idea

When I learned Python, I looked at several tutorials. Most of them are geared toward software developers—so you learn about data types, control flow (how to if/else and for-loops), classes, and other things that software developers use to build applications.

Most of the time, I’m not writing an application for hundreds or millions of users. I want to automate part of my job so I can reduce the mental load from the boring, manual tasks, and shift my focus to more important things. In other words, I need to write scripts more than I need to write applications.

So don’t Learn Python the Hard Way. Time is precious, why would you learn the hard way first?

The initial cost to start and how far those “tutorials” deviate from the daily data analysis need is probably why I’ve heard of so many false starts of Python among people that I knew. I don’t want to write a f-ing tic-tac-toe—it’s useless for my job and a total waste of my time.

The closest learning resource that fit my need was Automate the Boring Stuff by Al Sweigart. It’s an excellent book, and the online version is free, so I recommend checking it out.

Goal

I want to provide a tutorial so everyone that analyzes data and works with Email & Excel can use Python to automate the boring parts away.

Who doesn’t love a life of Email & Excel?

Who doesn’t love a life of Email & Excel?

The goal is, in 8 hours, the attendees will become 8% more efficient. If I code 20 hours per week, then over one year, 8% of efficiency gain means I can save 80 hours. How about using those 80 hours to take more walks and think about problems? Spend less time in front of computers—less eye strain, healthier, and more productive.

This tutorial is for people that analyze data daily, tried Python in the past because it’s hot, but for whatever reason never integrated Python it into their daily workflow.

I will not cover all the details. This is a tutorial on doing. It’s not a class.

My hope is that the examples will mirror some of the most common workflows that can be automated away in an analyst’s life. So by going through this tutorial, you can build a habit of recognizing repetitive tasks and writing a Python scripts to automate them away. The details can wait.

Why Python? What about R?

Here are my two cents: R is great for statistical programming, but Python is a general programming language and one that is much better at manipulating text than R.

I like R a lot. In fact, I still think modern R is a much better tool for the “crunching numbers” part of data analysis than Python. In this tutorial, however, I will focus on the strength of Python—being able to manipulate text and file system easily means you can write a lot of readable code and automate tasks that makes life easier.

Let’s take a look at the history of Python, in Guido’s own words

My original motivation for creating Python was the perceived need for a higher level language in the Amoeba project. I realized that the development of system administration utilities in C was taking too long.

That’s what Python is good at—building efficient tools without taking too much time and effort to code.

What are some tools that we can build, or things we can automate?

- Generate a report from a database in one click, complete with data and image

- Transform an excel spreadsheet (that has a fixed form) and load it to a database

- Email the reports once completed

- Retry if the report fails to run, then send a warning email if the retry fails again

- Schedule any of the above on a regular basis

- Write templates to reduce the amount of SQL code one has to change to meet a business requirement and make the code more readable

In other words, the difference between a person, A, who uses Python and who don’t, B, is that

- A will be more efficient than B—instead of going to office on Monday morning to compete with everyone’s query time, A can schedule the job early, kick back with a cup of coffee in hand, and read the report A first thing on Monday, before sending it out to business users.

My ideal Monday morning

My ideal Monday morning

- A’s works are more resilient to business logic changes—by writing templates (or code generators) that writes SQL queries instead of writing every bit of SQL queries by hand, the code becomes much more flexible, has less bugs, and will be easy to change in the future.

PyderPuffGirls Ep 1: Texts and files

Writing good code

What is good code? I would say that good code is readable code.

A good piece of Python code should be readable, as in reading with sounds. I can almost read through the whole code literally in plain English and understand what the code is trying to do.

Unless I’m running a time-consuming task like training a machine learning model, I would say that writing readable and maintainable code is way more important than writing high performance code. For the tasks I’m going after in this tutorial, human time is much more valuable than machine time.

So in this tutorial, I will try to make the code as readable as possible. Please feel free to suggest a different way of doing things if you think it will improve readability—I am learning too.

Let’s start by working with texts, or in Python terms, strings.

Manipulate text

In Python, texts are declared with single and double quotes.

person = 'Emma'

person2 = "Emma"

person == person2

prints

True

In line 3, I’m testing if the two variables are equal in value—there’s also something called ID, but it’s unimportant here—and they are. The only reason you may want to choose one over the other is when you have to escape quotes

word1 = "Y'all"

word2 = 'Y'all'

word2 spits out an error,

File "<ipython-input-2-4a7180725db2>", line 2

word2 = 'Y'all'

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

because Python thought the middle quote is part of the declaration, and it didn’t know what to do with the rest all'.

The good thing about Python is that you can concatenate strings and split them up easily:

part1 = 'I want to add'

part2 = 'strings together'

print(part1 + part2)

I want to addstrings together

The “+” operator concatenates the strings (and hence the missing space in the sentence.)

I can also split a string:

some_path = 'split/is/very/useful/for/file/paths'

print(some_path.split('/'))

['split', 'is', 'very', 'useful', 'for', 'file', 'paths']

The square brackets [] defines a kind of Python object call list. A list is just an list of values.

Escape strings

Escape strings starts with a \, this is for putting in special characters.

Some of the most common escapes include:

\n: newline character: it tells Python and most text editors to render a new line on screen when they see it.\t: tab: shows up a lot in tab delimited .csv files.\\: backslash: because Windows uses backslash for file path versus Unix’s forward slash.\', ‘": escaping the quotes to define a string. Says = ‘I don\'t even’- ‘\N{grinning face with smiling eyes}’: prints out a 😁. Yes, you can print emojis into the logs…

Raw strings and multiline strings

There is also raw text, defined by prefixing an r and multiline texts, defined by triple quotes—

raw_string = r"you mean now I don't need to escape? \o/" # double quotes because the "don't" part

multiline_string = '''now

I can write as many

lines

as

I want

'''

If you run multiline_string, you will see the string representation of multiline_string is actually

'now\nI can write as many\nlines\nas \nI want\n'

Comments

Anything that follows a pound sign (#, I guess you can call it hashtag too) is a comment in Python.

- For both Jupyter notebooks and PyCharm,

Ctrl+/toggles the selected lines as comments. This is very useful when developing code.

What about rendering variables in the string?

The action of plugging a variable into string is called “string formatting” in Python.

In some of the online tutorials and StackOverflow answers, you will see people use the C-style formatting with %s and %d etc. This is the “old way” of doing things. Please don’t use that in 2018 unless there’s is a very good reason to. Let’s use f-strings, a Python 3.6 feature which I will introduce when we talk about file manipulation.

Saving/Loading Files

In my opinion, when I learn a new programming language, the first thing I want to learn after knowing how to define a variable and run basic computations is to save the result. Computations are useless if they only lives in memory. So, in this section, I will show you how to save files.

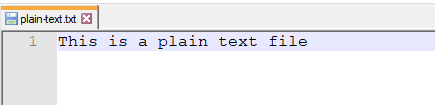

Python is great because I can read and write files easily. There are many kinds of files, but one way to categorize files is to see what shows up when we open it with a text editor.

Plain text

Binary

In other words,

- plain text: files that human can read when opened with notepad

- binary: can’t read

We will focus on plain text files for now.

Reading files

To handle files, you need to open it as follows. This particular way of opening a file is called a “context manager,” which will take care of closing the file after you do something for you. Otherwise, you will need to open(), write some data, and close() to make sure the change is saved and the file is not corrupt.

with open('some/path/to/file.sql', 'r') as f:

sql_query = f.read()

There are several things happened in the two lines of code:

open()is a function that returns a file handle calledf. It is a class in Python that we can use in the context to call the methodread(). A method is a function where the object itself is part of the arguments but hidden.- The

'r'stands for “read,” which is the default and can be omitted. Other options include'w': write—overwrites the content of the file if it already exists.'a': append—appends to the file

- Python uses 4 space indent to indicate control flow—control flow is a term for things like

if/elseandforloops andwhile—always set up your text editor or IDE so that it does not mix tabs and spaces. It will be very annoying down the road if you don’t! 99% of the people I knew uses 4-space indent, although I’ve heard of one case of 2-space indent too. - A context manager looks like

with doing_something() as some_handle: ..., which will take care “closing” for you. It is often used in file input/output and database connections. Use a context manager so DBA doesn’t yell at you! - When loaded this way,

sql_queryis a string.

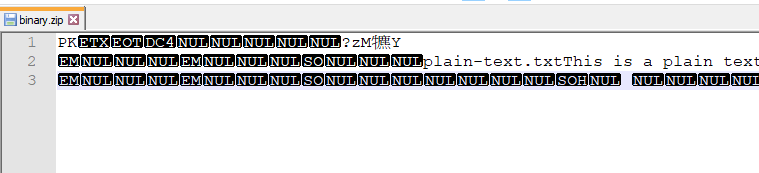

Writing files

To write back to a file

new_query = '''

select *

from some_table

where cake = 1

'''

with open('file2.sql', 'w') as f:

f.write(new_query)

This is what shows in the file:

Note that line 1 is empty and the file ends on line 5 because new_query starts with a newline character and ends with another.

Data files?

For data people, the most common file to deal with are

- csv, or comma separated value files

- excel spreadsheets

which I’d recommend loading with pandas:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv('some/path/to/a/file.csv')

Note that in Windows, folders are divided by backslash \, which is different from Unix’s forward slash /. This means in Windows you have to use double backslash \\ because the backslash itself is escaped in Python!

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv('c:\\some\\path\\to\\a\\file.csv') # absolute path that includes C drive

df.to_csv('c:\\some\\path\\to\\a\\file_output.csv', index=False)

For me, I prefer to wrap my path strings around an object from pathlib called Path and let Python handle which platform I’m running on for me. The Path object will automatically use / in Mac and \ in Windows, no matter who is running the script.

import pandas as pd

from pathlib import Path

file_path = Path('some/path/to/a/file.csv') # now this is platform agnostic

df = pd.read_csv(file_path)

Closing example for episode 1

Let’s write a SQL query that will always use yesterday’s date.

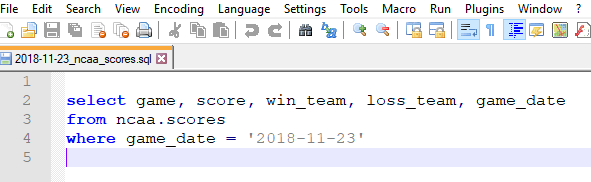

As an example, let’s say we are working with a NCAA basketball database ncaa. We can prepare a SQL script that

- Takes data from a table from yesterday

- Save to a file, where the file name tells us which day we are pulling the data from

First, we can use the datetime module in Python to get the date for yesterday

import datetime

yesterday = datetime.date.today() - datetime.timedelta(days=1)

When I run yesterday, I see

datetime.date(2018, 11, 23)

Now I can make a SQL query using what’s called a f-string (format string)

ncaa_query = f'''

select game, score, win_team, loss_team, game_date

from ncaa.scores

where game_date = '{yesterday}'

'''

- the f- prefix tells Python that this is an f-string. It means that it will fetch the variables defined inside and plug the value into it.

- In this case, the variable we want to fetch is

yesterdayspecified within the curly braces {}

Running ncaa_query, we see the string is rendered as

"\nselect game, score, win_team, loss_team, game_date\nfrom ncaa.scores\nwhere game_date = '2018-11-23'\n"

Now we can save it to a file

with open(f'{yesterday}_ncaa_scores.sql', 'w') as f:

f.write(ncaa_query)

and the result looks like

What’s next?

The PyderPuffGirls

- Episode 1: A Python Tutorial for the Bored Me

- Episode 2: How to Query a Database in Python

- Episode 3: Don’t Wait, Schedule and Relax Instead

Please feel free to post in the comments section or tweet at @ChangLeeTW for questions or comments.

†The name “PyderPuffGirls” came from Keith Finch. Thanks Keith!