Make a Workflow Config with YAML—PyderPuffGirls Episode 6

This post follows up on last post to introduce another convenient tool for writing maintainable code—the configuration file. In particular, I will show you a specific config file format, YAML, and how it works in Python.

Introduction

In the last post, I showed how to use Jinja2 to generate SQL queries from business logic. What if I have multiple files that share the same parameters? What if I have a project wide setting that I want to be able to change only once when needed?

This is where configuration file comes in.

Example of config files

I didn’t notice this pattern until a few months ago, but config files are everywhere.

Configuration file is a way to let users and developers change the behavior of a software without getting into the granular code details.

They also come in many formats. Here are some examples. Please scan through the files and see if you can get an idea of what those files are trying to do:

- The config for my blog uses YAML.

- The config for Airflow, a popular workflow engine for scheduling batch data jobs, uses TOML.

- A config for Counter-strike: Global Offensive, a popular video game, that uses a custom format.

Why config?

In the examples above:

- My blog is linked to my social network accounts by simply adding the handle.

- Airflow uses config to decide where the job logs should be, the address for web UI, how often does the scheduler refreshes, etc.

- Video games like Counter-Strike use configs to let players tune the control settings. The “Settings” inside the games often represents a graphical view to the underlying config files.

In all 3 examples, I may not see or understand the actual code, but it does not matter. As a user,

I can change the behavior of software without the code.

In other words, config file is a convenient abstraction. The business logic is abstracted away from the code as metadata for the users to change. Those config files improve user experience and reduce cost of maintenance—if I decide to link a different Twitter account for my blog, all I need to change is one line in the config.

The same idea applies to data analytics workflow. How to implement and where to store the metadata, however, depends on the context. Heck, just this week I found out that the best format to store the metadata in one of my project turned out to be an Excel spreadsheet.

So, I will not spend time on telling you what is the best way to write a config file. Instead, I will show you a particular format, YAML, so you can start playing with the concept.

A common format: YAML

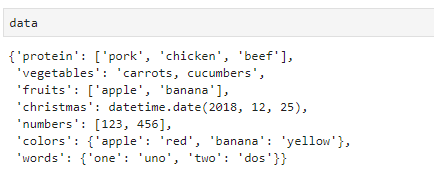

Here’s a yaml file. I use .yaml for the file extension, but people also use .yml. It is a plain text file that contains key-value pairs similar to Python dictionaries.

protein:

- pork

- chicken

- beef

vegetables: carrots, cucumbers

fruits: [apple, banana]

christmas: 2018-12-25

numbers:

- 123

- 456

colors:

apple: red

banana: yellow

words: {one: uno, two: dos}

YAML uses a nested structure with whitespaces to record the hierarchy in data.

It hates tabs—use whitespace indent only. I recommend using a 4-space indent like Python.

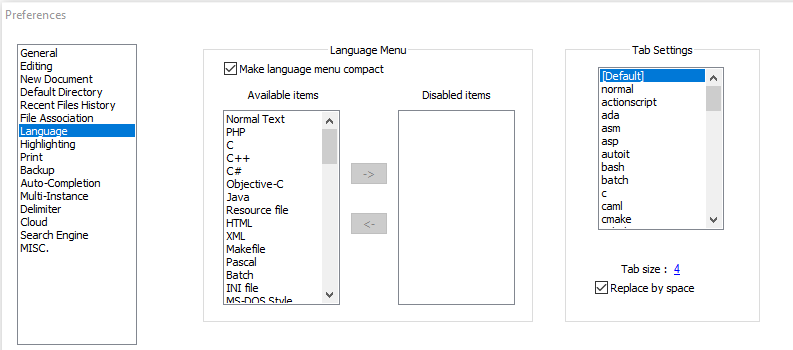

Most text editors allow me to replace tabs with whitespaces. For example, in Notepad++

YAML in Python

There are a few packages that can handle yaml files in Python.

I’m going to use PyYAML here because we are handling simple cases. If you ended up having to write complex YAML then StrictYAML may be a better choice.

To install PyYAML, run

pip install --user pyyaml

and to load, run in Python:

# not import pyyaml!

import yaml

Using YAML in Python

When I read the example above into Python,

import yaml

with open('d:/pyderpuffgirls/ep6/sample.yaml') as file:

data = yaml.safe_load(file)

this is what data looks like

The nested data becomes a Python dictionary. Now I can plug the values in the dictionary to my code—like what I did in the last post. That’s it!

Caution YAML has a list of reserved keywords in parsing—for example, yes becomes True and no becomes False. The full YAML syntax is a can of worms, so I will not attempt to cover it.

This is a good reference that should satisfy most of the data analytics needs, and when I use it, I stick to only the simple use cases—my goal is readable code, and I will not make my config so complex as to become unreadable.

A business logic example

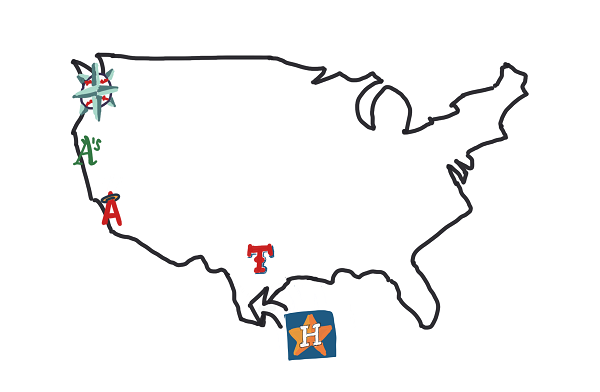

Let’s say it’s 2012, and I have a baseball business report that pulls data from all American League teams and aggregate by their division. In my configuration file, I might have

AL_East:

- Yankees

- Red Sox

- Rays

...

AL_West:

- Mariners

- Athletics

- Angels

- Rangers

In 2013, Major League moved the Houston Astros into the Americal League West, which made 5 teams in the division. This report now has to include the Astros. It is a business decision that the imaginary maintainer of the report have no control of.

Making changes in a complex report workflow due to change in business logic is probably the most underappreciated job in analytics. Even more so when people think it’s a small change in business, and therefore “can’t you just change this one thing and give me the report now?”

The good new is, if I had set up my code with a configuration file that captured the correct business logic, then all I needed to do is change one place. In my example, adding “Astros” to AL_West should be enough. There would be no need to modify the code.

Learning abstractions

Business is complex, and it rubs off on analytics. This complexity in business has to live somewhere in the code. I can choose to let it live inside a single file, or I can abstract it away into a separate text file from the code.

It is up to me to decide whether to add this layer of abstraction or not. If I decide to use a config file, then I am adding one more file to the project, so the complexity in structure goes up. But does the overall project complexity go down? Everything has a tradeoff. In the end, it boils down to one question: “does it help the project or not?”

The answer clearly depends on the context. To me, the real benefit of learning new abstractions is that abstractions give me options. Just a year ago, I wasn’t aware of config files. Learning to apply it has changed how I view code. Today, I have the options to ask those questions.

I learned about config files from the chapter on Metaprogramming in The Pragmatic Programmer. There are many other types of abstractions that I can apply to my code. I believe that spending time to read about timeless concepts pay off—it helps building a habit to think about problems from different angles, which is more valuable than learning one trick in a particular coding language.

What’s next?

Let’s look into what can I do with Excel in Python next time.

More PyderPuffGirls