Don't Wait, Schedule and Relax Instead—PyderPuffGirls Episode 3

The purpose of automation is to let machine do things while us humans rest. In this post, I will show you how to schedule a job with a Python module schedule.

Requirements

The tool I’m using here is a Python module called schedule.

To install, run

pip install --user schedule

Using schedule

Here is a working example. Suppose that I have a sql_job that I want to run on every Sunday at 5:00 PM, then I can write

import schedule

import time

def sql_job():

print("I'm pretending to be a SQL job!")

schedule.every().sunday.at('17:00').do(sql_job)

while True:

schedule.run_pending()

time.sleep(1)

Let’s break it down.

Defining jobs, or Python functions

In schedule, what I meant by a job in the do() is, in fact, a Python function.

A Python function is define with the def keyword.

A Python function is defined by its input and output. I may go into more detail about Python functions later. For now, let’s keep it simple.

Warning — scope of variables

In Python, there is a concept called variable scope. I think it is easier to understand by examples—what happens when I have 2 functions that share the same variable name in their definitions?

Case 1

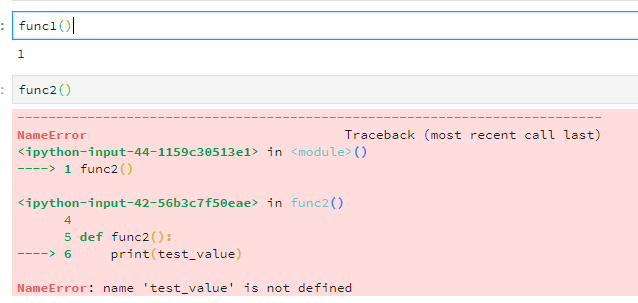

In a clean Jupyter notebook where test_value has not been defined, if I define

def func1():

test_value = 1

print(test_value)

def func2():

print(test_value)

then func1 finds test_value inside itself and prints it out. But when I execute func2, Python doesn’t know what to do with it—it doesn’t know what the test_value means in func2. The variable is not in the function’s scope.

Case 2

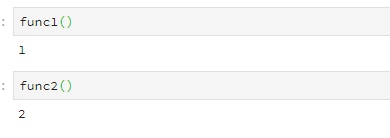

Let’s try again. This time, I will define test_value outside the functions:

test_value = 2

def func1():

test_value = 1

print(test_value)

def func2():

print(test_value)

Here’s what I get when I execute the two functions.

As I can see,

func1ignores what I defined outside and getstest_valuefrom itself.func2does not havetest_valueinside so it gets the value from outside.

In writing Python code, scope issues (some people call it namespace) can lead to annoying bugs.

However, this is why people use an IDE like PyCharm. In a few weeks, I will make a short introduction to IDE and demonstrate why coding in an IDE helps avoiding scope issues. It is 2018, and there is no reason to write Python in a text editor unless necessary.

One input, multiple inputs, default values

In the case of func1 and func2 above, if a function has no input argument, then Python assumes the function can find all the variables—either within its definition or from outside—to get the job done.

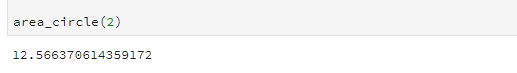

Most of the time, I’d like to have an argument in my function. For example, I can calculate the area of a circle from its radius:

import math

def area_circle(radius):

area = math.pi * (radius ** 2) # ** stands for square. math.pi is the value of pi

return area

area_circle(2)

Running the code gives me

Note: The naming convention for functions in Python is using all lowercase and underscores.

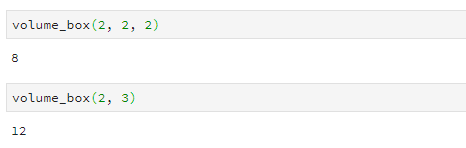

I can also define a function that takes multiple arguments as input and set default values.

def volume_box(length, width, height=2):

return length * width * height

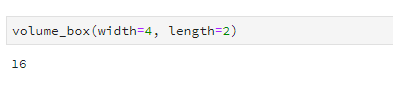

In this case, the default value for height is 2. If I put in volume_box(2, 3), it works the same as putting in volume_box(2, 3, 2) because Python supplies the missing argument with the default value.

Another thing that I can do is passing the arguments by their names (keywords). If I do it this way, then I can change the order of arguments:

Not returning anything

Every function has to return something in Python. But what happens when I skip the return statement at the bottom?

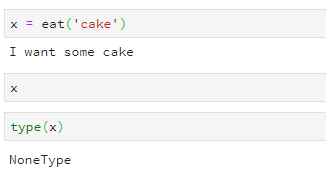

For example, I can print out what I want to eat today:

def eat(food):

print(f'I want some {food}')

When I check what this function returns

x = eat('cake')

x

it shows nothing. In fact, it returns a NoneType, or a None object (the NULL object in Python) by default.

Instead of leaving it out, I would say it is better to

Use pass instead

The effect of leaving out return is the same as adding a pass at the bottom. I think this is a better approach when I don’t want to return anything because making the intent clear means more readable code:

def eat(food):

print(f'I want some {food}')

pass

Putting code into a script

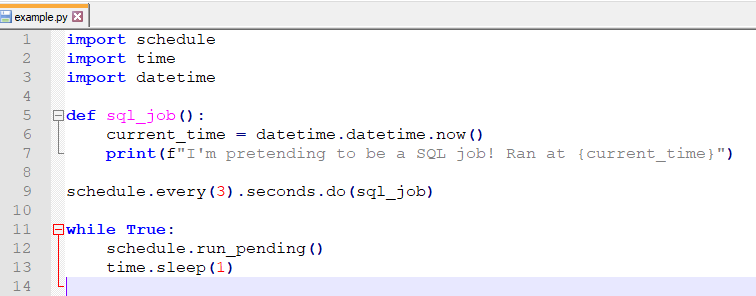

So far, I have been running everything in a Jupyter notebook. To schedule jobs, it is easier to put things inside a Python script that ends with the file extension .py.

Let’s say if I have this piece of code:

import schedule

import time

import datetime

def sql_job():

current_time = datetime.datetime.now()

print(f"I'm pretending to be a SQL job! Ran at {current_time}")

schedule.every(3).seconds.do(sql_job)

while True:

schedule.run_pending()

time.sleep(1)

Then I can save the whole things as example.py and execute it.

What is that time.sleep thing in the code?

It is used to prevent the infinite loop while True to use up all the resources of the CPU. See the comments below this StackOverflow answer.

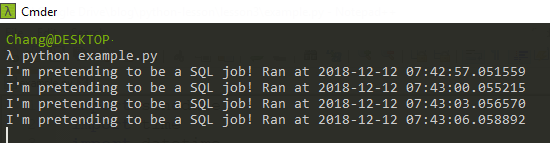

Running a script

To run the Python script, open a

cmd.exe(in Windows), or- Cmder, a console emulator in Windows, or

- Terminal in Mac

then run

python example.py

and move the window somewhere and leave it running—don’t close it!

If you want to interrupt the execution, press Ctrl+C on Windows (sometimes Ctrl+D or Ctrl+Z, just try everything.)

Note: to run the script on a remote Unix server that does not have a graphical user interface, one way to keep the it running without putting the process to the background is using the command line tool screen. I will show you how to use screen in another post.

Note (12/12/18): I realized I still haven’t get to a master post on solving the “python command not found issue” yet, so bear with me here. I’ll come back and fix it!

Trick for later

There is a small trick that you will see in a lot of Python modules. I can modify my code to this and it will still run the same.

import schedule

import time

import datetime

def sql_job():

current_time = datetime.date.now()

print(f"I'm pretending to be a SQL job! Ran at {current_time}")

if __name__ == '__main__':

schedule.every(5).seconds.do(sql_job)

while True:

schedule.run_pending()

time.sleep(1)

The benefit of adding __name__ == '__main__' is that I can import sql_job into another piece of Python code.

If I have time, I want to talk about how to package Python code, so I think it is reasonable to put it out ahead of time. This is a great StackOverflow answer that explains what this line does.

An example for better Mondays

Let’s say I have a SQL query that generates a business report for delivery on Monday mornings. I know the data is usually in the database on Monday by 2:00 AM, so I should be able to get the report while I’m sleeping. Therefore, I want to schedule my job on every Monday at 2:00 AM to

- execute a SQL command and get the result back, then

- save the result to a file with the Monday date in the filename.

It makes my Monday better because I don’t have to run the query first thing on a Monday morning, hoping that my query runs and will not fail after two hours. I can just check the result and see if I need to make changes or investigate before sending it out.

The code

This is an example that builds on top of what I showed in the last post, How to Query a Database in Python.

I am going to call this scheduling script weather-report.py, which selects the daily high and low temperature from every city in the last 7 days.

import datetime

import schedule

import time

import os

def get_weather_report():

"""

Makes a 7-day weather report before the Monday report date.

"""

report_date = datetime.date.today()

start_date = report_date - datetime.timedelta(days=7)

end_date = report_date - datetime.timedelta(days=1)

weather_query = f'''

select city, temp_lo, temp_hi, date

from weather

where date between '{start_date}' and '{end_date}'

;

'''

username = os.environ['PSQL_USERNAME']

password = os.environ['PSQL_PASSWORD']

engine = create_engine(f'''postgresql+psycopg2://{username}:{password}@localhost:5432/mydb''')

df = pd.read_sql_query(weather_query, engine)

df.to_csv(f'{report_date}_weather_report.csv', index=False)

print(f'Finished report for {report_date}'.)

if __name__ == '__main__':

schedule.every().monday.at('02:00').do(get_weather_report)

while True:

schedule.run_pending()

time.sleep(1)

Now I just need to open up command line and run

python weather-report.py

on Friday and come back to my report on Monday.

Questions

What about logging?

In this post, I only used print statements to print to screen and skipped saving the logs to a file. Most of the time, I only care about the logs if my job fails. Therefore, I am going to introduce logging when I talk about how to send emails with attachments in Python. Not today.

There is a logging module in Python, but tuning the logger levels will be out of scope for this tutorial.

What about other scheduling tools?

There are a plenty of tools out there for scheduling. For example,

- in Unix, there is

Cron - in Windows, there is

Task Scheduler

Another option is using a workflow engine, such as Apache Airflow. In my opinion, however, the workflow engines out there are more or less designed for production batch data jobs that run for many hours.

I chose schedule because my goal for this series of tutorials was to provide the easiest configurable tools to automate the boring data stuff away. I do plan to write a supplemental post on how to use Cron and Task Scheduler and the tradeoffs later, but for now, let’s stick to the simple option.

What if my machine crashes?

This section is a work in progress

Cron solution

If it is a remote Unix machine that is maintained by IT and you already know how to use Cron, try using the @reboot special string in crontab to make sure the Python script is executed after the system reboots. For example, see this question. I will cover Cron in another post.

What’s next?

In the next post, I will show you how to email the results and close the boring report cycle.

The PyderPuffGirls

- Episode 1: A Python Tutorial for the Bored Me

- Episode 2: How to Query a Database in Python

- Episode 3: Don’t Wait, Schedule and Relax Instead

Please feel free to post in the comments section or tweet at @ChangLeeTW for questions or comments.