Document Analysis as Python Code with Great Expectations

If you have pulled your hairs out fixing the performance of a model built by someone else and at the same time wondering “why is this happening to me?”, then this post may be for you.

The nightmare

The following story is one of the worst nightmare in data science:

- A model that has been working for months started to lose its performance.

- Management saw the drop in a dashboard and started asking why.

- But this model was built by someone who has left the company.

You spent weeks debugging, only to find out that it was due to a small change in business logic change that you are not aware of. The performance drop came from the fact that the data has been in a different state than before.

You couldn’t go back doing what you were doing because there was time pressure. As a result, you lost the momentum on your own project.

Even worse, no one thanked you for fixing the model because it was supposed to work in the first place.

It was a lose-lose deal from the outset and everyone was upset.

Is my problem in the data or somewhere else?

Is my problem in the data or somewhere else?

What is the problem

The problem comes down to one thing:

Building a new model is easier than maintaining a model

and the knowledge of the builder did not pass down to the maintainer.

When I build a new model, I probably spend more than 60% of my time understanding all the edges in my data to curate a dataset for my model. There are lots of insights gained about business in this process.

Where did those insights go? Jupyter Notebooks, of course. Even if I remember to write down all my findings, which is questionable, this process still creates a problem.

No one is going to read through all my notebooks when the model is given to somebody else

Automate the knowledge transfer

This is one of the hardest problem in a data science team–how do I transfer knowledge?

If I spend 80% of the time on exploratory analysis, then I should be able to capture and automate my insights into code, so the next person that takes on my project can

- read through the code to gain the same insights, and

- see a warning when bad things happen and check against what I already know about the data.

But there was no good tool that handles this problem. Most of the teams I know monitor the data pipeline with their own tools, and there is no consensus on how to transfer knowledge of this kind. Unit test does not help–the problem is not in the code but in the data.

Comes Great Expectations

great_expectations was the first Python package that I saw that was perfect for this task. It came from a tweet:

What tools exist for automated monitoring of incoming data that are oriented at data scientists/engineers?

— David Robinson (@drob) August 9, 2018

Like unit testing for data: e.g. "Yesterday the completion rate of courses dropped by 90%"

I'm aware of one, Great Expectationshttps://t.co/2YA0hKI5mb

After playing with it, I can say that I loved this package and the idea behind it. Therefore, in this post, I will cover the absolute basics of getting started.

Goal

My goal for this post is to show you how to

- set basic expectations and save the config, and

- load expectations and validate on a new dataset.

Installation

- Project page: https://github.com/great-expectations/great_expectations

pip install --user great_expectations

Throughout the post, I will use great_expectations as ge:

import great_expectations as ge

Data

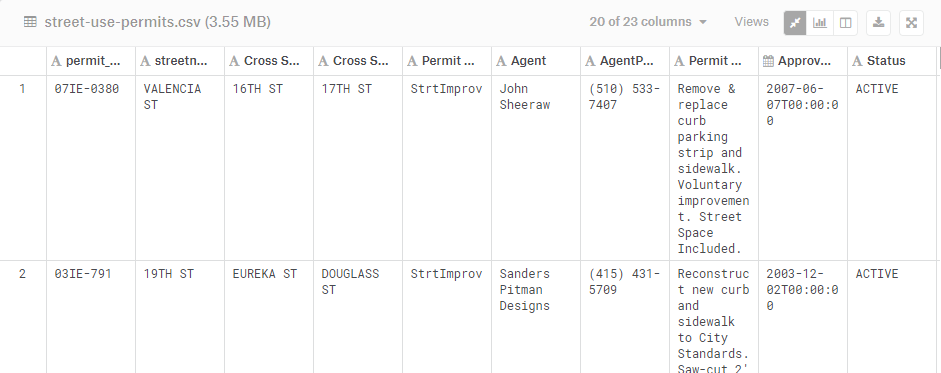

The dataset I’m using is a Kaggle dataset called San Francisco Street-Use Permits. I picked this one because I wanted to find a real life dataset that can emulate the situation I have in mind. In this case, let’s say I have a model that uses Permit Type as a feature, then what if the city government started issuing a new type of permit? How can I catch that change in my data pipeline?

Using Great expectations

The idea behind great_expectations is that each dataset should be paired with a set of expectations—they are tests for data during runtime.

The library does not throw an error if a new batch of data in the dataset violates the expectations, as how I want to use this piece of information depends on the context. Depending on the situation, I might

- Reject the new batch of data, and only use the old and validated ones

- Raise a warning in the logs

- Send an email at 3 AM to the person on call for the pipeline to take a look

But it is unlikely that I want to throw an error and stop the whole pipeline.

Steps

- Loading data

- Setting an expectation on a

pandasdataframe - Exporting and importing expectations

1. Loading data

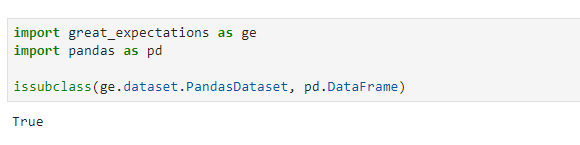

For now, great_expectations sits on top of pandas and pair the expectations with pandas dataframes. So the first step is to convert a pandas dataframe into a great_expectations dataframe (i.e. making a subclass.)

Therefore, I can still use all the methods like .head(), .groupby() for my dataframe.

There are two ways to load a dataframe into great_expectations:

Method 1: Read from a csv

df_ge = ge.read_csv('sf-street-use-permits/street-use-permits.csv')

Method 2: Convert from pandas dataframe

This is undocumented, but it is what ge.read_csv is doing under the hood.

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv('sf-street-use-permits/street-use-permits.csv')

df_ge = ge.dataset.PandasDataset(df)

Both of them will give me df_ge, which is a great_expectations dataframe for me to set expectations. I use method 2 more because most of my data is in .parquet.

2. Setting and getting expectation

An expectation is a runtime test that has no meaning unless paired with a dataframe. There are many built in expectations

or I can write my own

Here, I will only demonstrate a simple expectation

expect_column_values_to_be_in_set

by taking a subset of my dataframe df_ge with only 2 permit types, then set an expectation to validate the street use permity type by:

- Setting the expectation to cover only 1 out of 2 permit types to see how it fails.

- Setting the expectation to cover both permit types to see how it passes.

permit_subset = ['Excavation', 'Wireless']

df_excavation_and_wireless = df_ge[df_ge['Permit Type'].isin(permit_subset)]

The dataframe df_excavation_and_wireless has 4505 rows and two permit types:

- Excavation

- Wireless

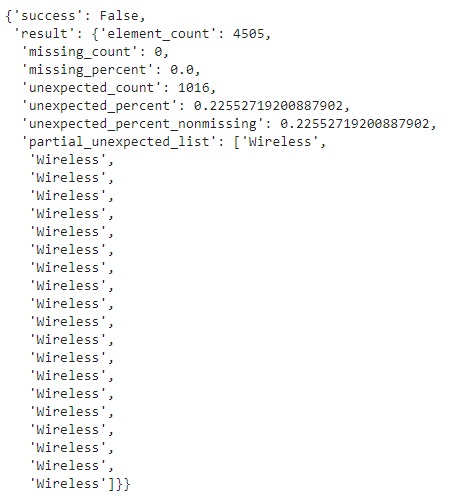

Failed

When I say that this dataframe should only contain 1 permit type Excavation, then it fails:

fail_type = ['Excavation']

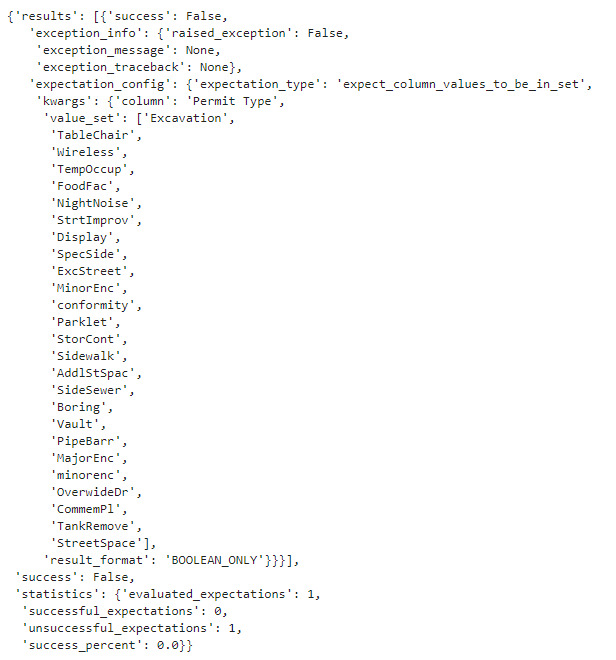

df_excavation_and_wireless.expect_column_values_to_be_in_set('Permit Type', fail_type)

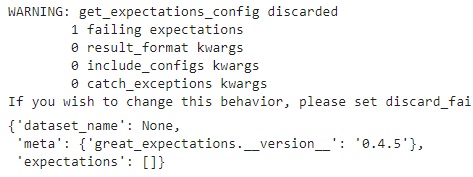

When I try to get the expectation config from the data,

df_excavation_and_wireless.get_expectations_config()

Pay attention to the empty list of expectations in the config. In this case, the expectation I added did not pass, and great_expectations discards it afterwards. If I really want to get it into my config, then I can take a subset the dataframe and force this expectation to pass on the subset instead.

Succeeded

And if I set the expectation to cover both permit types instead, it succeeds

success_type = ['Excavation', 'Wireless']

df_excavation_and_wireless.expect_column_values_to_be_in_set('Permit Type', success_type)

df_excavation_and_wireless.get_expectations_config()

This time, the passed expectation is stored in the expectation config for me to reuse.

Exporting and importing expectations

After I set the expectations, I want to save them so I can reuse on new data, so I need to export and import my configs.

Exporting

All passed expectations are stored in the config that is paired with the dataframe. I can either

- export it into a Python dictionary, or

- save it as a json file

# as dictionary

config = df_excavation_and_wireless.get_expectations_config()

# as json file

df_excavation_and_wireless.save_expectations_config('ew_config.json')

I can also wipe my saved expectations:

df_excavation_and_wireless.remove_expectation()

Importing

To import and use the expectation config, load the json file as dictionary and pass it into the .validate() method:

For example,

import json

with open('ew_config.json') as file:

validate_config = json.load(file)

df_excavation_and_wireless.validate(expectations_config=ew_config.json)

A workflow example

Let’s go through another example to demonstrate all the points that I said I will cover:

- Loading data

- Setting an expectation on a

pandasdataframe - Exporting and importing expectations

In this example, I break my data into two pieces:

- the “before” data:

df_pre, and - the “after” data:

df_post,

to simulate the situation of having new data (post) coming into the pipeline built on old knowledge (pre).

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv('sf-street-use-permits/street-use-permits.csv')

df_ge = ge.dataset.PandasDataset(df)

df_pre = df_ge.sample(3500, random_state=1234) # 3500 rows for pre-data

df_post = df_ge[~df_ge.index.isin(df_pre.index)]

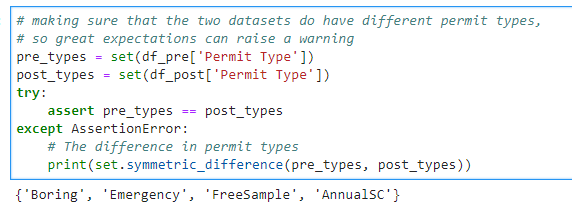

I know that the set of Permit Types in those two dataframes are different

pre_types = set(df_pre['Permit Type'])

post_types = set(df_post['Permit Type'])

try:

assert pre_types == post_types

except AssertionError:

# The difference in permit types

print(set.symmetric_difference(pre_types, post_types))

but let’s see how great_expectations catches this change.

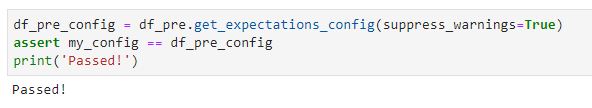

Setting expectation and save

First, I will set the expectation on the before data, then export to expectation to a file:

possible_permits = df_pre['Permit Type'].unique()

df_pre.expect_column_values_to_be_in_set('Permit Type', possible_permits)

Then save the expectation to saved_config.json:

df_pre.save_expectations_config('saved_config.json')

Load expectation and validate

Now I can load the expectation and validate on the post data df_post.

import json

with open("my_config.json") as file:

saved_config = json.load(file)

Note that this gives me the same config as what I had:

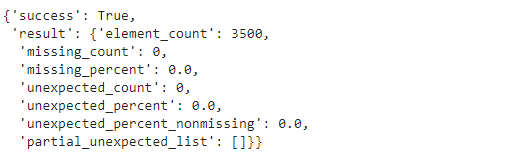

Finally, I can validate with this config on df_post:

df_post.validate(expectations_config=my_config, result_format='BOOLEAN_ONLY')

I am using the BOOLEAN_ONLY result format so it doesn’t print out everything, but there are other result formats with more detail. You can find possible formats in the documentation:

Follow-up questions

These are the question that I am working on:

- What are “high value expectations?” In writing software tests, there are low value tests and high value tests. Can we generalize the idea to expectations?

- What’s the best way to integrate this into a workflow that relies mostly on SQL/Hadoop instead of Python?

- How do I use it with Airflow or any other workflow engine?

If you have experience in any of the above, please let me know.

Additional resources

- Down with pipeline debt: This article is written by the

great_expectationsteam to describe the problem they faced that prompted them to start working on this package. - The Slack channel for Q&A and support

Other thoughts

-

In my discussion with Eugene Mandel, who works with Abe Gong and James Campbell, the main authors of the library, he said that each expectation is a falsifiable statement—now I feel like I’m doing science.

-

I see this as an extension of Design by Contract and programming with assertions from software engineering but in the context of data.

-

The package’s name comes from Charles Dickens’s novel of the same name. The protagonist in the book is Pip. So, if you google

pip great expectationsyou will not see a single entry about Python. Search for something else.

I’d love to hear your thoughts and stories on this. What do you want to know? Please leave a comment below ⬇️ or tweet at @ChangLeeTW.