Becoming a Better Data Scientist: Testing with pytest

This story has happened to me too many times: First, I started a project. Then I explored relevant data and wrote some code that fulfills business needs. I was proud of my code and the initial results.

My code looks great!

My code looks great!

A few days later, the business came back and asked for additional work due to the things they saw in the data. So, I made changes to my code and pushed the results. A few days later, they came back again. This time they want to revert the changes from last time and add a few more things. And there would be more, and more, and more.

In time, the size of code grew with the requests and became a beast due to all the things that I didn’t think of when I first started. Eventually, one particular ask will break everything—now I have to revisit thousands of lines of code from two months ago so I can patch it up and meet this new request.

This simple request would take me hours. And it wasn’t because coding was hard. The change was time consuming only because I wanted to make sure that I did not breaking anything. Even if it was a small request, more often than not I had to send an email that says: “give me 2 days.” And my business partner would wonder “why does it take two days?”

What I didn’t tell them was that I had the same question—why did it take me two days? 😒

When business logic strikes

When business logic strikes

So, after a few frustrating experiences like this, I started looking for software best practices. One thing that I learned was testing.

In this post, I want to talk about tests and introduce a Python testing library that I use, pytest, as the first post in a series. This series of posts will be my reflection on how to invest a small amount of time now to save a large amount of time in the future.

Testing

There are many reasons why having a test practice produces better software, but I’ll only provide one reason that helped me:

Test cases are development logs

One benefit of writing test cases is that they serve as a small story for new visitors of the code. They are like examples that people can read and understand what had happened in the past.

In other words, it is easier to read the test cases and find out what a piece of code does than reading the code itself.

Code is only a tool to solve problems. For data science, I care more about what data goes in and what kind of data comes out—and that’s what good test cases do. In the test cases, inner working of the functions and methods are less important, but all the arbitrary business reasons are captured by examples with good reasons in the comments.

Scenario: when a new member joins a project, which option takes less time for him or her to figure out what is going on?

- Read 1,000 lines of SQL to figure out what the script does.

- Read the test case that describes the input and output of said script.

To me, the answer is 2.

By the way, that new member (aka that sucker) is often me in two months 😂. I’d rather live my data science life on easy mode.

Another benefit of having tests as documentation over writing a separate documentation for developers is that tests are part of code. Life happens and I don’t always remember to update the documentation after a hotfix. But if my code breaks something in the test, it forces me to update and keep it current.

The testing problem in data science

In software engineering, unit tests (in particular, regression tests) are the most common form of tests.

For a large portion of data science that overlaps with software engineering, I think unit tests should be put in place. However, much of data science is exploratory work where there is no defined specifications. In my opinion, for data science work, testing on data or rather, testing the properties of data, is often more valuable than testing the code itself.

There are many things that data scientists can discover in the process of building a data prototype. One common discovery is learning about a business logic change that was previously unknown to anyone on the team. If I fought hard to gain insights to the data, then I should capture those insights as high value tests.

How can I capture those insights and write checks for future data? That will be the topic in another post when I go into Great Expectations. For now, let’s introduce pytest.

Pytest

Perosnally, I don’t want to spend too much time writing tests in data science. A test has no value if my code doesn’t go into production, so I would rather spend more time exploring. But they can still be valuable to me during development if the cost is low enough. I want to write as little boilerplate code as possible.

For this purpose, pytest is great because its syntax allows us to write low cost tests. In my opinion, a pytest test costs me much less to write than a unittest test (I have not tried nose, which another common framework), and that’s why I like it so much.

How to Install and Use pytest

To install pytest, I’d use pip:

pip install pytest

To use pytest, navigate to the root folder of where the test code is, then run

pytest # search and run all tests in the folder and subfolder

Let’s say I want to test everything under the folder src, then I can move to src by cd src and run pytest there. It will search through all the files that has the prefix test_ or suffix _test in the filename for tests.

src

├───integration_tests.py

├───code_module1

│ └───tests

│ └───test_my_function.py

└───code_module2

└───tests

└───test_your_function.py

I can also run only one file or one test by specifying the filename, like

pytest src/tests/test_my_function.py # only run tests found in test_my_function.py

pytest src/tests/test_my_function.py::test_number_1 # only run test_number_1 in the file

Command line options

There are also command line options, the most common one that I use are

-s: print standard out in suammry-v: verbose mode-k: run tests specified by keywords.-lf: last failed. When specified,pytestwill only run the tests that failed in the last run.--showlocals: show local variables when there is an error.

Writing tests

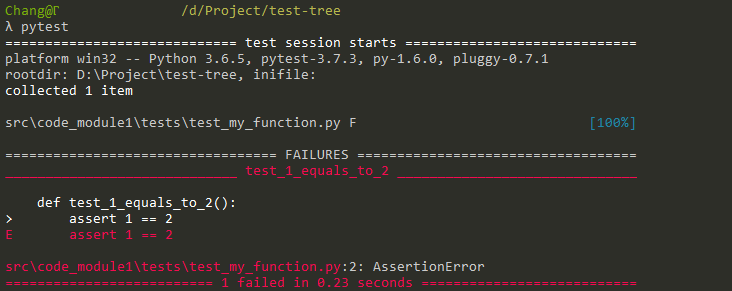

pytest differs from other testing libraries in Python in that I can write functions instead of classes for my tests. As an example, I can put

def test_1_equals_to_2():

assert 1 == 2

in test_my_function.py and run pytest to see the test failure.

Adding test data

To build a test case, I need to make up some test data. I think it’s better to keep the data in the code, especially for tests that describe my past mistakes, so they always get committed and not treated as separate data into the code repository. I have tried a few ways to bundle data together with the code:

1. From csv, but as string

I think this is the most readable form to make test data—in fact, I can paste the string to Notepad++ or Sublime or even Excel to get nicely formatted data without having to move between files.

from io import StringIO

import pandas as pd

name_data = StringIO('''Name,Gender,Count

Emily,F,21389

Emma,F,19107

Madison,F,18612''')

names = pd.read_csv(name_data)

2. From json

I can also convert from json strings. Most of the time it comes from the to_json() method after I explored a dataset in Jupyter Notebook.

For example, in the data above, running names.to_json() prints

{"Name":{"0":"Emily","1":"Emma","2":"Madison"},

"Gender":{"0":"F","1":"F","2":"F"},

"Count":{"0":21389,"1":19107,"2":18612}}

and I can use StringIO to load it as a pandas dataframe:

from io import StringIO

import pandas as pd

names2 = pd.read_json(StringIO('''

{"Name":{"0":"Emily","1":"Emma","2":"Madison"},

"Gender":{"0":"F","1":"F","2":"F"},

"Count":{"0":21389,"1":19107,"2":18612}}'''))

3. From flat files

Finally, I can store data as files read from the disk:

- as

csv: plain text, probably the best option for small dataframes - as

pickle: binary, Python only format - as

parquet: binary, keeps the data format, requires eitherpyarroworfastparquetto load

What’s next?

So I covered installing and how to write 1 != 2, but there wasn’t a concrete example.

I hear you—I was going to put more things in this post, but the length of the post was getting out of hand. In the next few posts, I will show a few things that I learned using pytest, including:

- writing tests for pandas

- how to set up fixtures—or how

pytesthandlessetUp()andtearDown()for me - writing tests for PySpark

- pipeline tests to reduce pipeline debt—or how to document my data intuitions

- what not to test

But before that, I’d love to hear how you implement tests in your workflow as well. Please feel free to leave a comment or tweet at @ChangLeeTW and start a discussion.