Untangle the SQL Mess with Jinja—PyderPuffGirls Episode 5

Writing and maintaining complex SQL query sucks. How can I use Python to make my life easier?

The problem

Writing SQL code

One of the most boring task in analytics is dealing with a repetitive SQL query that comes from business requests. I’ve used this workflow many times:

- First, I looked at the data and realized that there was a piece of code that, with a slight change in one place, had to be repeated at least 20 to 30 times.

- Then, I selected and pressed Ctrl+C to copy that part of code and proceeded to smash my Ctrl+V 20-30 times in said section.

- Finally, in each pasted chunk, I went in and changed the part that needed to be changed.

That sounds pretty good. But here are some scenarios that could happen next:

- 90% of the time, I would find an error in the data pulled by the query. Now I have to go back and check each line to find out where I made the mistake.

- 10% of the time, the code just worked.

Scenarion 2 was more terrifying than 1. I knew there’s a boogeyman in my code, but my computer wouldn’t tell me where to find him. It would take two or three more checks before I have enough confidence in shipping my result.

Even worse than writing SQL code

There’s one thing that is worse than writing a complex and repetitive SQL code:

Maintaining someone else’s complex and repetitive SQL code.

Maintaining a piece of SQL code that screams Ctrl+C and Ctrl+V is a nightmare. Sometimes I would look at a folder of SQL queries full of the dreaded Ctrl+C and Ctrl+V pattern that needs to be changed for a new business request. I sighed. Then I discovered who wrote this bunch of queries six month ago—oh wait, it’s me!—and that made me go through 5 stages of grief:

- Denial: This can’t be right. Did I really write this?

- Anger: Why did I sign up to do this piece of crap? [Multiple expletives]

- Bargaining: Also known as delegating (i.e. abusing your coworkers)—hey, can you do me a favor and look at this?

- Depression: I will never be able to finish this project on time. There’s just no way.

- Acceptance: It’s all part of life. This is what data science is about. (Proceeds to troll new grads entering into data science on the internet.)

Is that really it?

A tangled mess

A tangled mess

What can I do?

Unreadable SQL queries suffer from two symptoms

- The business logic that goes into creating this query is hidden in clutter.

- It is difficult to make changes—how do I know I’ve changed all the places I needed to change for even a small request?

What’s the cause? I say that the causes are

- SQL code is often way too verbose due to business logic, and

- the business logic is tied into the code itself. If the business logic changes in one place, then several places in the code have to change.

In the last few episodes, I showed you how to automate boring tasks that require moving and clicking the mouse. Are there things about SQL query that I can automate to solve those problems?

The answer is yes, and the solution comes from one of the most liberating principle in programming—

Write code that writes code

With Python, we can highlight the part of code that we care, and let computer write the boring part for us. I am going to demonstrate this principle with a Python package, jinja2, so let me show you an example first.

An example

Here is a typical query in Postgres that I used on the IMDB 5,000 movies dataset.

There is a field in the dataset called genres that contains the genres of a film like this:

| movie_title | genres |

|---|---|

| Avatar | Action|Adventure|Fantasy|Sci-Fi |

| The Social Network | Biography|Drama |

| Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince | Adventure|Family|Fantasy|Mystery |

| Jerry Maguire | Comedy|Drama|Romance|Sport |

| The Fast and the Furious | Action|Crime|Thriller |

This storage format saves disk space, but it is not ready to use for analysis. My goal is to transform this field into a more convenient format.

Creating flag columns

In this case, I want to remove the pipes (|) from genres and create a bunch of flag columns that turn my table into

| movie_title | Action | Adventure | Drama | Fantasy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avatar | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| The Social Network | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Harry Potter | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| … | … | … | … | … |

In other words, I want to flag films by genres. A film gets 1 in a genre if it belongs in said genre and 0 otherwise.

The SQL code

After finding out all the possible values for genre, this is how I would write the code in PostgreSQL:

with genres_split as (

select movie_title, genres, regexp_split_to_array(genres, '\|') as genre_array

from movies

)

select movie_title

,genres

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Thriller'] then 1 else 0 end as thriller

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Film-Noir'] then 1 else 0 end as film_noir

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Western'] then 1 else 0 end as western

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Animation'] then 1 else 0 end as animation

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['War'] then 1 else 0 end as war

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Family'] then 1 else 0 end as family

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Adventure'] then 1 else 0 end as adventure

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['History'] then 1 else 0 end as history

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Musical'] then 1 else 0 end as musical

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Biography'] then 1 else 0 end as biography

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Horror'] then 1 else 0 end as horror

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Reality-TV'] then 1 else 0 end as reality_tv

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Action'] then 1 else 0 end as action

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Comedy'] then 1 else 0 end as comedy

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Documentary'] then 1 else 0 end as documentary

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Romance'] then 1 else 0 end as romance

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Fantasy'] then 1 else 0 end as fantasy

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Drama'] then 1 else 0 end as drama

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Sci-Fi'] then 1 else 0 end as sci_fi

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Sport'] then 1 else 0 end as sport

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Mystery'] then 1 else 0 end as mystery

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['News'] then 1 else 0 end as news

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Crime'] then 1 else 0 end as crime

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Music'] then 1 else 0 end as music

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Short'] then 1 else 0 end as short

,case when genre_array @> ARRAY['Game-Show'] then 1 else 0 end as game_show

from genres_split

;

Let’s do it again in Python.

Python: templating with Jinja2

Jinja2 is a popular templating engine for Python. To install, run in command line

pip install --user jinja2

A template engine can be think of as a programming language (Jinja) inside a programming language (Python). Jinja2 is most used in Django template for making websites and web applications, because web development can be repetitive with a lot of similar code. I mean a lot of similar code—and that’s why it can help me write SQL.

A tour in the Python Jinja

A tour in the Python Jinja

Basic usage

Here’s how I view the workflow of Jinja2:

- Define a Python string that contains Jinja syntax as my template

- Define the parameters that I want to fill in the template

- Render the template as an output string.

In other words, if I have a run_sql function that can execute a SQL command in some database, then my code will look like the following

from jinja2 import Template

template_string = '''

some_template

'''

list_param = [some list, ...]

dictionary_param = {some_key: some_value, ...}

output = Template(template_string).render(param1=list_param, param2=dictionary_param)

run_sql(output)

Example revisited: flag the genres

Let’s work through the IMDB movies example I put on the top of this post.

The Python code

from jinja2 import Template

# split a string into a list

genres = '''Thriller

Film-Noir

Western

Animation

War

Family

Adventure

History

Musical

Biography

Horror

Reality-TV

Action

Comedy

Documentary

Romance

Fantasy

Drama

Sci-Fi

Sport

Mystery

News

Crime

Music

Short

Game-Show'''.split('\n')

# Postgres does not support dashes in column names, replace with underscore

def lower_and_replace_dash(word):

return word.lower().replace('-', '_')

# Creating and populating a dictionary from a sequence (genres) like this is called dictionary comprehension

genre_mapping = {

lower_and_replace_dash(genre): genre

for genre in genres

}

# This part is Jinja

genre_template = '''

WITH genres_split AS (

SELECT *, regexp_split_to_array(genres, '\|') AS genre_array

FROM movies

)

SELECT movie_title

,genres{% for key, value in genres.items() %}

,CASE WHEN genre_array @> ARRAY['{{ value }}'] THEN 1 ELSE 0 END AS {{ key }}{% endfor %}

FROM genres_split

;

'''

output = Template(select_template).render(genres=genre_mapping)

print(output)

And Python prints out the same SQL code that I wrote to create the flag columns!

Why this is good

What do I see in this Python code compare to the pure SQL code? I would say

- In the Python code, the list of genres is on the top—it is clear that this query is about the genres.

- The Jinja2 template shows that I’m doing the same thing (CASE WHEN flags) for all genres—there will be no surprise.

In this code, making changes is easy because the business logic—which genres to plug in—is separated from the code logic—what do I want to do with the genres.

Now let’s break the code down.

Jinja: use the curly brackets

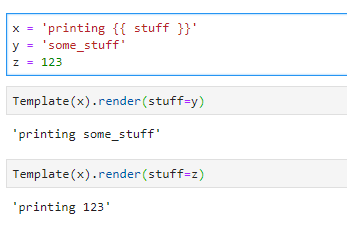

There are two kinds of curly brackets in Jinja2: {{ kind1 }} and {% kind2 %}.

- A double brackets

{{ stuff }}means it will look for the variable that is passed intostuffwhen rendering and substitute with said variable’s string representation:

- A single bracket with percentage sign

{% keyword %}means I’m using a specialkeywordfrom Jinja2. They are often control flow keywords likefor,if, orblockthat come in pairs withendfor,endif, etc.

In the example where I used Jinja syntax,

# This part is Jinja

genre_template = '''

...

SELECT movie_title

,genres{% for key, value in genres.items() %}

,CASE WHEN genre_array @> ARRAY['{{ value }}'] THEN 1 ELSE 0 END AS {{ key }}{% endfor %}

FROM genres_split

;

'''

output = Template(select_template).render(genres=genre_mapping)

genres.items() is a sequence that puts out two variables key, variable at a time, and they are substituted into END AS {{ key }} and ARRAY['{{ value }}'] respectively.

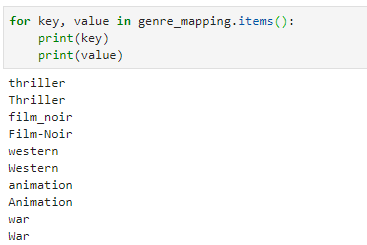

What does genres.items() do? Note that it is rendered from the Python variable genre_mapping, so what it really means is genre_mapping.items(). Let me print out the key and value of genre_mapping.items() so I can see what is substituted (cropped the image to the first few):

If I compare the result with the code with the SQL code, then I can see that it follows the same order. Jinja2 is simply putting the items into their places!

Python and Jinja

The idea behind templating is to extract and highlight the important business logic then let computer write the boring code for you. Jinja is a powerful template engine, so covering even 50% of what it can do will be out of scope.

Everything about making a template can be found in the Jinja Template Designer Documentation, but I will list a few things that I found that I’m using over and over when constructing SQL queries.

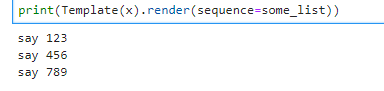

1. Loops

The thing I used the most is probably a loop. A loop is made up with an opening and an ending:

some_list = [123, 456, 789]

x = '''{% for number in sequence %}say {{ number }}

{% endfor %}

'''

print(Template(x).render(sequence=some_list))

2. If statements

Another common keyword is if. It is also made with opening and closing a if bracket. I can put any comparison in it to use with my for loop:

some_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

x = '''{% for number in sequence %}{% if number > 4 %}say {{ number }}

{% endif %}{% endfor %}

'''

print(Template(x).render(sequence=some_list))

3. Special variables in Jinja loops

Sometimes I want to build a WHERE statement. In all the SQL dialects that I know, WHERE clause conditions are separated by ANDs. But making a loop means I will end up with something like this

WHERE

AND condition_1

AND condition_2

...

AND condition_n

that has one extra AND on the top.

To avoid this, I can use the loop.first special keyword in my loop

flag_columns = ['thriller', 'film_noir', 'western']

where_clause = '''

WHERE {% for column in columns %}{% if not loop.first %} AND {% endif %}{{ column }} = 1{% endfor %}

'''

output = Template(where_clause).render(columns=flag_columns)

print(output)

and it prints out

WHERE thriller = 1 AND film_noir = 1 AND western = 1

Those special variables are great in handling edge cases like this. All the keywords are listed in the Control Structures section in the Jinja Template Designer Documentation.

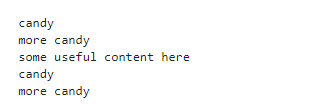

4. Blocks

How do I reuse a block of text? In other words, is there a way to define a variable inside Jinja? The answer is yes, and one way to do so is using a block with the set keyword:

stuff = '''

{% set candy %}candy

more candy{% endset %}

{{ candy }}

some content here

{{ candy }}

'''

print(Template(stuff).render())

What I did was that I made a block called candy that only lives inside the template, and I can reuse it many times in the same template. Templating a template 🤔.

5. Two loops?

One thing I found was that, if I have nested loops, then the loop.first or loop.last keywords only pick up the innermost loop. In other words, Jinja is not aware of any parent loops when it is executing the inner loop code. This is a behavior that I want to avoid.

To refer to the outer loops, I can to store the loop with a different name. Paraphrasing the Jinja2 documentation, this is what I would do:

template = '''

{% for stuff in loop1 %}

some stuff

{% set outerloop = loop %}

{% for more_stuff in loop2 %}{% if not outerloop.first and if not loop.first %}

some more stuff

{% endif %}

{% endfor %}

{% endfor %}

'''

Now Jinja knows I want to skip some more stuff at the very first iteration of the nested loops.

6. Removing white spaces for prettier rendering

Jinja has a way to remove trailing spaces and newline characters using the minus sign (-). This means that I can indent the for loops like Python and print out formatted SQL. I will link two things here:

Note on templating

The wrong way to use templates

Writing code that writes code is a powerful idea. But it is so powerful that sometimes I take it too far, as it was very tempting to rewrite all my SQL queries with a template. The lesson I learned?

Don’t.

It may not be worthwhile. This is what people called premature optimization. Don’t make a template if you are only going to use it once.

Compare before you buy

Let’s imagine that I added another 500 lines of code to my movie genres SQL query that uses the genre flags in some way. I have two possible ways to code:

- Write everything in a single SQL file

- Write my SQL query in a Python template, and render the code into another SQL file using a dictionary of genres.

In 6 months, if I need to

- add or remove a genre due to business requirements, or

- explain to other why this piece of code is made this way,

which one will be easier for myself?

This is the criteria I use to judge whether I should make a template for a piece of code. If I can see it will be a pain in the ass in a few weeks, then it’s worthwhile to clean it up.

A good template highlights what is important in the code. It reduces clutter and helps me understand what this query is trying to say.

So when should I make templates? For me, if it will make me hate my life less in the future, then I will do it.

Further reading

I read about templating SQL with Jinja2 from a post on the StitchFix engineering blog two years ago:

but the concept didn’t stick until I read the chapter on Code Generators in this book:

and it transformed how I see programming. It’s an old book (published in 1999) so the technology in the books feels outdated. The timeless chapters on principles, however, gave me more insight than any other programming book that I’ve read so far in my career. I will talk about what made the code generator concept stick in another post.

What’s next?

In the next post, I will cover another concept that will make complex code maintainable: configuration files.

In particular, I will use a library called PyYAML, that reads a configuration file format called yaml (/ˈjæməl/).

More PyderPuffGirls

Please feel free to post in the comments section or tweet at @ChangLeeTW for questions or comments.